As readers will know non-native pacific ocean pink salmon (Onchorhynchus gorbuscha) appeared in numbers in many UK rivers this summer. The occasional pink salmon had turned up in Scotland in the past, including a single specimen caught in the lower Spey in 2015, but almost always in very low numbers. The origin of these strays is considered to be from stocking carried out in northern Russia (as far back as the 1950s). The initial stocking in Russian waters appeared to fail but from 1985 “odd year” spawning stock was introduced into rivers in the White Sea area. Self sustaining populations quickly developed resulting in an expansion into Finnish and Norwegian rivers soon after.

The most likely explanation for the widespread incursion in 2017 was that these northern Europe stocks had a very good year; this tendency to expand their range during a bumper year is a known feature of pink salmon ecology.

This blog is to report on the egg monitoring trials we were involved with in conjunction with Marine Scotland Science (MSS), and other rivers, but before that I will provide a brief summation of the situation on the Spey.

On the 10th July the first rod caught fish was reported from the lower Spey. Over the next few weeks another 10 or so rod caught fish were reported including as far upstream as Abernethy, over 80km from the sea.

A fresh run pink salmon caught in the lower Spey in July 2017

A cock pink salmon caught in the Spey at Abernethy, 81km from the sea, on the 17th July by Scott Bruce. As far as we are aware this is the furthest upstream that a pink salmon had been recorded in Scotland.

On the weekend of the 12th August pink salmon were reported to have been seen spawning in several rivers in the NE of Scotland and on the 14th August SFB staff counted ten pink salmon redds in the Spey below Fochabers with redds also reported by ghillies further upstream.

Pink salmon redd in lower Spey on the 14th August. Note the summer vegetation on the banks, a distinct change from the autumn foliage normally associated with salmon spawning in the Spey.

Following these reports of spawning a number of actions were taken by Government and fishery boards including redd destruction on some rivers. The Spey considered that it was important to gather data on the incubation of these eggs in the river which led to our participation in a national monitoring programme coordinated by MSS. This programme ended up rather limited in extend with only the Spey and the Ness able, or willing, to collect eggs from redds.

Prior to the eyed ova stage salmonid eggs are susceptible to disturbance with sharp movements such as knocks resulting in high mortality. We therefore had to wait until a sufficient period of time had elapsed after spawning for the eggs to reach the eyed stage. Subsequently on the 6th and 9th Spey we managed to excavate 200 live eggs from two redds in the river. These eggs were then placed in two secure incubators which were buried in the gravel on opposite sides of the river.

Pink salmon eyed eggs collected from redds in the Spey on the 9th Sept 2017. The eyes of the developing embryos can be seen clearly inside the eggs.

The incubators provided by MSS. The eggs were placed in the chamber on the chamber on the left. The incubator was then buried so that the other chamber remained just on the surface. A yellow temperature logger was also secured to the incubator to record the temperature within the riverbed gravel. Another temperature logger recorded the temperature at the surface.

One of these incubators was then lifted occasionally to check on the development of the eggs. On the 9th October, on the first inspection, we found that there were only 7 live alevins (out of 100 eggs) remaining in the incubator. The incubator was also full of sand, which may have contributed to the high mortality.

Some of the few surviving alevins recorded in the incubator one month after installation. To this date the mortality rate was 93%. A few dead eggs can be seen top right.

The surviving alevins were placed back in the incubator which was buried again in the gravel. On the next visit, on the 30th Oct, only five live alevins were found, the other two had died. However it was clear that the pink salmon alevins were developing well, and as expected given the relatively mild temperature regime of the Spey this autumn.

By the 30th Oct the alevins were developing well with pigmentation along the flanks, the yolk sacs getting smaller on each visit.

The next inspection on the 13th November found that the yolk sac absorption was almost complete on the most advanced alevin and they were developing the characteristic silvery pink sides.

A well advanced pink salmon alevin on the 13th November 2017.

The last and final visit to the incubators was made on the 27th November when it was found that there were only three live alevins with another recently deceased. The most advanced at this point were on the point of becoming fry as they had absorbed virtually all the yolk sac. The trials were terminated then but the alevins were virtually at the point of becoming fry (when they leave the gravel as free swimming fish and when they have to feed for themselves for the first time).

The remaining three pink salmon alevins at the end of the trial. The most advanced was ready to emerge as a free swimming fry. Note how thin the fry had become, an adaption to enable them wriggle up through the gravel when they are ready to emerge.

On closer inspection back at the office it was noted that the ventral slit on the most advanced fry was almost but not quite “zipped up”.

The yolk sac was virtually all gone with the skin of the alevin/fry closing to seal the underside of the belly.

The other, undisturbed incubator was also lifted on the 27th November. None of the 100 eggs placed in this incubator were found to have survived to the fry stage. There was no evidence on sand entering this incubator so the 100% failure rate was unexplained. The excavation of the eggs from the redds combined with the incubator may have contributed to the high mortality rate in the trial, or was this high mortality rate typical of that experienced by the other other pink salmon eggs in redds in the river? It was interesting to read that in the River Ness trials all the eggs died during incubation.

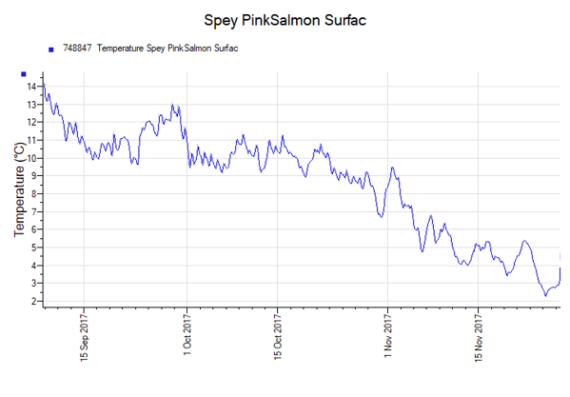

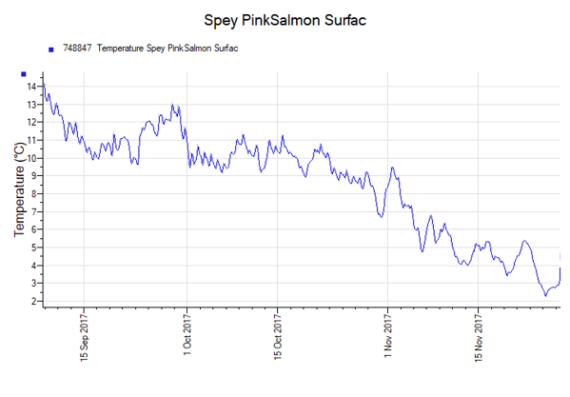

The temperature loggers associated with the trial were downloaded the same day. The temperature profile was one of almost continual decline (as expected during autumn) with the temperature falling from 14oC in early September to 2.5 by the end of the trial.

The readings from the surface temperature logger at the end of the trial.

So whilst we should be cautious about concluding too much about survival of the pink salmon eggs under natural Scottish river conditions we did learn a great deal about the development and incubation. It is clear that the pink salmon developed as expected, although perhaps taking a little longer than anticipated. We have still to download other temperature loggers in the area; when we do so we will have the full temperature regime during the entire period, from spawning to fry emergence. However, this is likely to be around 1100 degree days (e.g. 110 days at 10oC), which is longer than occurs in their native Pacific rivers range, probably a consequence of the declining temperature profile as opposed to the more natural decline followed by increase in the spring.

So there we have it, a UK first for the the Spey. As far as we are aware this is the first time that pink salmon eggs have been monitored to the fry stage in a UK river. The survival rate was very low, the incubation a little longer than anticipated, but the timing of spawning was months earlier than our own native Atlantic salmon. The key question now is whether those fry which do emerge will be able to make the transition from dependency on the resources provided by the mother through the yolk sac to feeding for themselves. They will emerge from the redds into a frigid and relatively barren River Spey. They are supposed to migrate immediately to the sea, where the temperature will be a little warmer but not exactly teeming with life at this time of year. However, this is the world’s most successful salmon species; we would be foolish to think that they will all perish.

The post Pink salmon egg trials appeared first on Spey Fishery Board.

Spey Fishery Board